Case Study: Pediatric Feeding Tube Weaning

By: Tracy Huppert, MEd CCC-SLP, Spectrum Pediatrics, LLC

Introduction

Based on research, it has been found that infants and children born preterm and/or at-risk are often suffering from emotional, behavioral, and self-regulation disturbances. These disturbances include long-term feeding tube dependency, feeding disorders, and post-traumatic stress due to invasive, intensive medical care early in life.

Pediatric tube feeding, a medical need for numerous pre-term and medically at-risk children, is used when a child is unable to eat by mouth in order to gain an adequate amount of food and liquids for survival. Through tube feeding, such as a gastric tube (G-tube) or nasogastric tube (NG-tube), it is ensured that a child will receive adequate caloric/fluid supply and gain sufficient weight. Tube feedings also provide the benefits of protection from aspiration caused by dysphagia, a break for families from stressful feedings, and allowance for easy transmission of non-palatable medications via the tube. Nonetheless, there are also problems that develop with tube feeding a child. Some complications include decreased swallowing activity, frequent vomiting, obesity, reduced hunger-driven motivation to eat, and financial and emotional stressors. These factors can contribute to difficulties with feeding disorders and self-regulation.

A feeding disorder can be defined as a disturbance in oral intake that cannot be explained by a medical diagnosis. Frequent symptoms include food refusal, regurgitation, gagging, or swallowing resistance. A feeding disorder is a common early-onset disorder in the pediatric population. The estimated prevalence ranges from 5-35% in healthy infants and toddlers (Benoit, 2001).

Self-regulation, another area of development that is affected by preterm or at risk birth, refers to a child’s ability to respond and adjust to the changing demands of their environment. Self-regulation can be observed through a child’s fluctuations in temperament, arousal, and behaviors. It is theoretically assumed that eating and drinking are dependent upon self-regulation, yet regulation capacity is suppressed by tube feeding. In order for sufficient oral eating to be established, tube feeding must be significantly reduced. Only when tube feedings have been reduced or terminated can a feeding disorder be differentiated from other disorders or diseases. When the underlying feeding disorder is understood, effective treatment can begin.

The child’s relationship with food can be altered through decreasing use of the feeding tube, treating the feeding disorder and addressing the emotional trauma of early, invasive medical care. Treatment focuses on reestablishing a child’s self-regulation and experiences of hunger and thirst in order to normalize the child’s relationship with food.

Case Presentation

The patient is a 2 year 6 month old male who was born full term and weighed 9 pounds and 1 ounce. He was delivered via emergency C-section due to uterine rupture. He experienced a lack of oxygen at birth, which caused damage to the basal ganglia area of the brain. A Cerebral Palsy diagnosis was given based on his medical presentation, including difficulties with motor movements and swallowing.

In his first two months of life, the patient was in the NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit) of a local hospital, where he experienced a variety of medical setbacks, including seizures, two bouts with pneumonia, consistent aspiration and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD). He was given medication in order treat reflux and seizures. A nasogastric tube (NG-tube) was placed a few days after birth to provide an effective means to feed the child based on his medical difficulties with reflux, aspiration, and motor movements. A gastric-tube (G-tube) was inserted approximately 1 month after birth, yet a staph infection caused it to be removed, and the NG-tube was inserted again. The patient underwent surgery for another G-tube placement in June 2009. From approximately 6 months of age to 2 years three months of age, he obtained the majority of his nutrients via the G-tube and none by mouth.

From birth to the time the child started the tube weaning program, the patient had been working with numerous pediatricians, medical specialists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, and speech-language pathologists on his feeding skills. In the few months preceding the tube weaning process, the patient initiated play with food, asked what was on the table, attempted to get food in his mouth, and occasionally gestured to communicate that he wanted to taste food. The child presented with significant oral motor challenges, including decreased bolus formation, oral transit and a prominent tongue thrust. His weight was in the 25th-50th percentile as measured by US norms for children with cerebral palsy.

The tube weaning program is composed of four phases – Evaluation Phase, Hunger Induction Phase, Intensive Phase, and the Follow-Up Phase. Prior to beginning the tube weaning program, the client had to undergo a thorough intake and evaluation conducted by the tube weaning specialists, an occupational therapist and psychologist specializing in feeding disorders. The intake included a medical records review, multiple videos of feeding sessions, and a conference with the parents to discuss the feeding issues, current amount of oral intake, medical conditions, and developmental status. When analyzing the medical records, the wean team had to be able to determine the previous indication for the tube feedings and the traumatic impact of previous medical treatments. A modified barium swallow study (MBSS) was conducted to determine that eating by mouth would be safe for the child. The MBSS revealed no signs of aspiration or imminent risk of aspiration. The patient was also screened for possible medical complications, including hypoglycemia, feeding intolerance, failure to thrive, that may impact the overall success of the wean. Based on the presentation of the client, he was deemed to have a safe swallow, and he did not present with any indications of medical difficulties that would make the feeding tube weaning unsuccessful.

A group of professionals was then assembled to prepare for the intensive tube weaning program. The parents were involved in all aspects. A pediatrician was also involved in order to write the orders for the tube weaning program and monitor his medical status and weight throughout the nutritional intake changes. A speech-language pathologist, occupational therapist, nanny, and feeding specialist were also vital team members.

Management and Outcome

After the Evaluation Phase is complete and the tube weaning team has been established, the Hunger Induction Phase and Intensive Phase will follow. After both phases are completed, the tube weaning team’s goal is to achieve all intake via mouth rather than a G-tube. In the weeks and months following the tube weaning program, the child and family should continue to incorporate more and more foods and textures into the child’s repertoire. During the Follow-Up Phase, the family will also consult weekly with the tube weaning specialists to ensure that the child’s feeding habits continue to improve.

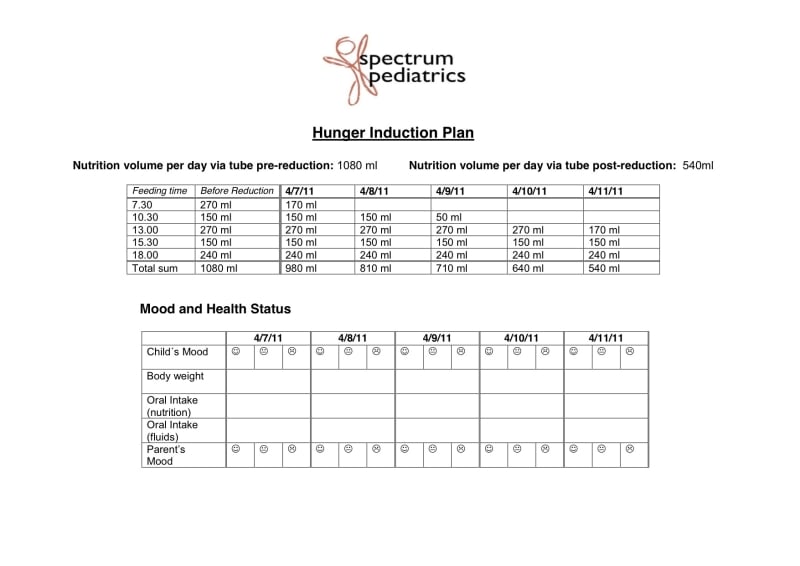

As described, the first phase of the tube weaning program was the Hunger Induction Phase. The plan for the tube weaning program was based on the child’s medical history, and it was individualized for the needs of the child. It lasted for approximately 5 days. During this time period, the client’s volume of nutrition given via tube feeding was slowly reduced. The following chart exhibits the daily alterations to the client’s intake from 1000 ml to 500 ml.

The patient in this case study began to develop a stronger interest in food as his blenderized diet intake via G-tube was decreased. He began to consistently request for food and to try more items, including Nutella, Honeycomb cereal, Gerbers Lil’ Crunchers, ice cream, popsicles, and whipped cream. He did not exhibit any interest in drinking at this time, despite his newfound curiosity in some foods. The team combatted this issue by beginning to offer foods that were naturally full of water like fruits and popsicles. A blender was used to puree foods. Solid foods like cookies and crackers were kipped into blenderized foods and enjoyed by the child. During the phase the child was only able to retain about 25% of food he attempted to eat due to tongue thrust and inefficient oral skills. This meant meal times lasted for long periods of time and resulted in frequent presentations of food throughout the day. Sleep was difficult for the patient during this time as his intake through the tube was decreased. The hunger cycle and sleep cycle are closely linked, and they are impacted with changes in either area.

The second stage, the Intensive Phase, in which the child had minimal or no nutrition from the G-tube to develop self-regulation with hunger and thirst, lasted for approximately 14 days. This phase was home-based in the child’s natural environment and followed his natural circadian rhythm. The team members utilized intuition and developmental knowledge in order to read the “cues” of the patient to know what the child wanted to eat, as well as with whom and where. All of the eating scenarios were very relaxed and focused on fun and play. The tube weaning program team members were cognizant of ensuring an eating environment that was comfortable and low-anxiety. If the child was ever afraid to eat, the therapists and parents would return to enjoyable play activities. He was able to cope with his post-traumatic feeding disorder and its negative effects through play in the low-stress, enjoyable environment.

After two days in the Intensive Phase, the patient began to lose weight, which was expected based on the decreased tube feedings. The team considered the child’s weight loss to be too detrimental to his health if 10% or more was lost. He lost 1.5 pounds, which was approximately 7-8% of his total body weight. It was determined that in order to keep the patient in a safe weight range that he would be supplemented with bolus feedings just prior to nap and bedtime. A doctor was consulted, along with the team members, when making this decision. Despite the fluctuations with the patient’s weight, he was beginning to self-regulate and understand the feeling of hunger. He would point to his button of his G-tube close to feeding times in order to gesture that he was hungry. This recognition of the sensations associated with hunger was a first in the life of the child.

The patient continued to exhibit changes in his hunger and sleep cycle on the third and fourth day of the tube weaning program. He had difficulties with sleeping based on his new sensations with hunger and self-regulation. The team continued to make the eating situation as comfortable as possible for the patient by “following his lead”. This led to feedings of his most desired foods and in a variety of locations, including outdoors, indoors, on the floor, in the bathtub and in the car. The team also continued to provide water-dense foods, such as melon and cantaloupe, in order to ensure that he was keeping well hydrated. It was evident that he was growing in his familiarity with new sensations, foods, and oral motor skills.

The patient began to develop an appetite and a natural hunger cycle by the fifth day of the Intensive Phase. He ate 2 granola bars dipped in whipped cream for breakfast, along with a few bites of egg salad. For lunch, the patient consumed approximately 6 tablespoons of peanut butter on sugar wafer cookies. Due to his continued difficulty with swallowing water, the therapist would provide drops of water in between bites to successfully manage sticky and difficult foods. The tube weaning program team also began to provide the patient with 4 ounces of blenderized food flushed with four ounces of water at his bedtime. That ensured a good night sleep for the child, as well as the family, which made for more successful days. The supplemental blenderized food and water via G-tube also guaranteed that the patient would not get dehydrated. If he did not have enough liquids, there was a higher chance for him to get sick, which would require the feeding tube wean program to be terminated.

By the seventh day of the tube weaning program, the child continued to exhibit some difficulty in establishing a natural sleep cycle, yet his weight was beginning to improve. He weighed 27.2 pounds prior to the tube weaning program. After approximately 3 days into the Intensive Phase, the doctor measured a weight of 25.8 pounds. After one week had passed of eating orally, the child weighed 26.45 pounds.

The Intensive Phase continued for another 5 days, and the team continued to let the child experience hunger and make the choice to be an “eater” by mouth. At this point the patient had reached his approximate starting weight of 28 pounds. At the end of the intensive phase of the tube weaning process the child’s oral motor skills had improved so that he was retaining 50-75% of foods presented orally. As a result of this increased oral motor efficiency meal times became much shorter.

After the Intensive Phase of the tube weaning program is completed, the Follow-Up Phase is required. The family continues to keep a food log, have weekly weight checks at the doctor’s office, and occasional blood work as needed to determine that the child is continuing to show positive, safe growth. This information is shared with the tube weaning program specialists on a weekly basis for the next 6 months in order to ensure a continued safe transition into oral feedings. It is also essential that the child exhibit that he can maintain oral eating habits during a time of compromised health or stress, such as illness or a major transition. At present, the child is continuing to gain weight and obtain 100% of his nutrients by mouth.

Discussion

The distinction between feeding disorder and feeding problem may not be clear. Feeding problems are a common and, to some extent, normative behavior in most children. They may refuse to eat, gag during swallowing, or “pocket” food in their mouths during some period of their lives. In most cases, these symptoms can be explained by dislike of a certain taste, temperature or texture of food, and the feeding problems dissipate over time. If there is a short period of problematic feeding for which there is a known cause (e.g. after reflux, medical event), the feeding behavior should normalize. If it does not normalize, even after a full recovery, a feeding disorder may be present.

There are specific criteria that need to be present in order for a feeding disorder to be diagnosed. Typically, the feeding situation is often stressful for the parents and the child. A calm and satisfying feeding routine cannot be established by the caregivers. Another criterion of a feeding disorder is that the feeding situation is extremely disturbed, which results in symptoms such as: failure to thrive, growth retardation, oral motor apraxia, and a disturbed parent-child relationship. Another criterion is that the child should have the symptoms listed above for at least three meals a day for more than four weeks.

There is also a need to clarify the differences between a G-tube and an NG-tube. A nasogastric tube (NG-tube) passes through the nostrils, into the esophagus, and into the stomach. It is usually only in use for a short period of time. A gastric tube (G-tube) is placed directly into the stomach through an incision. Typically, it is used long-term for feeding difficulties.

Another question that may arise from this case study is the concern about what foods are offered during the tube weaning program. The team usually follows the lead of the child by introducing multiple foods and observing which food(s) the child shows interest in during the feeding s. It is also imperative that the meal participant(s) working with the child are also eating. Once the tube weaning program is concluded, the family and tube weaning specialists can focus on a wider array of foods to meet the child’s nutritional needs. During the tube weaning program, the most important factor is having the child develop the sensation of hunger and meeting that need through oral feedings. The nutritional value of the food is not essential at this time. The tube weaning team merely wants to the child to enjoy the feeding experience and create positive feelings with food. A well-balanced diet can be addressed after the child is an established “oral eater”.

From this case study, it can be surmised that by reducing the caloric intake from tube feedings, treating the emotional anxiety related to feeding/oral activities through play, and allowing the child to “lead” in feeding situations, there is a strong likelihood that a child with a feeding tube can become an oral eater.

Table

Here is a sampling of foods that the child was eating prior to, during, and after the tube weaning program.

(*denotes fed by G-tube; – denotes fed by mouth)

Pre-Tube Weaning Program Sample Diet:

– A few Gerber’s Apple Wagon Wheels & Honey Nut Cheerios

*240ML blenderized food flushed with 120ML of water

– 5 Goldfish Crackers

*180ML blenderized food flushed with 120ML of water

– 5 Veggie Chips

– 2 chocolate cookies

*180ML blenderiezed food flushed with 120ML of water

– Sucked on barbeque chicken cubes, broccoli florets, and an onion ring dipped in ketchup

– Sips of cow’s milk from cup

*240ML blenderized food flushed with 120ML of water

Mid-Tube Weaning Program Sample Diet:

– 2 granola bars dipped in whipped cream

– Few bites of egg salad

– 6 Tablespoons of Jif Peanut Butter on sugar wafer cookies

– Drops of water from a straw in between bites of peanut butter

– Few chicken nuggets

– Few licks of cherry popsicle

*4oz. of blenderized food flushed with 4oz. of water

Post-Tube Weaning Program Sample Diet:

*180ML water, ½ tsp Kids DHA Omega 3, Udo’s Choice Children’s Probiotic, 1 Children’s Multivitamin

– 2 packets of Quaker instant oatmeal mixed with 2% milk (0% loss on his bib)

– Sips of water by straw

– ¼ cup applesauce

– 3 Nabisco honey graham crackers with 2 Tbsps. Creamy Jif Peanut Butter

*120 ML water

– 1 4oz. container of StonyField Yo Baby 3-in-1 Meal of Apple and Sweet Potato yogurt

– 1 chicken finger

– 2 French Fries

– Few bites of a hot dog with a bun

– Sips of water

– Bisco Sugar Wafer Cookies with ends wrapped in Fruit by the Foot

– 10 White Cheddar Cheeze-Its

– 1 ounce V8 Splash Fusion from Avent bottle

– 1 ounce Square West Soy Teriyaki flavor tofu

– 2 Tsps. pureed zucchini and olive oil

– 1 4oz. container of Hunt’s Jello Snack Pack Butterscotch Pudding

– 3oz. 2% milk from Avent bottle

*120ML water

Acknowledgements

The authors of this case study would like to thank Dr. Markus Wilken. His knowledge and research of post-traumatic stress and feeding disorders has greatly shaped the ideas presented in this case study.

The consent of the client’s family to share this information regarding the Spectrum Pediatrics tube weaning program is also appreciated by the authors.

References

The information for this case study was gathered from the following:

Benoit, Diane, Sheri Madigan, Sandra Lecce, Barbara Shea, and Susan Goldberg. “Atypical Maternal Behavior Toward Feeding Disordered Infants Before and After Intervention.” Infant Mental Health Journal 22.6 (2001): 611-26. Cambridge Health Alliance Home Page. Cambridge Health Alliance. Web. 23 May 2011. .

Institute for Psychology and Psychosomatics of Early Childhood Home Page. Markus Wilken, PhD and Martina Jotzo, PhD. Web. 24 May 2011. .

Wilken, Markus, PhD and Jennifer Berry. “Pediatric Feeding Tube Weaning: A Child-Directed Approach to Establishing Oral Eating After Feeding Tube Dependency.” Spectrum Pediatrics, Alexandria, VA. 8 Apr. 2011. Lecture.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient and patient’s family for publication of this case report and accompanying tables and food logs.

Futher Information

For further information regarding the feeding tube weaning program, please contact Spectrum Pediatrics, LLC at 703-299-0051 or [email protected].

This Month’s Featured Author and Organization: Tracy Huppert, MEd CCC-SLP, Spectrum Pediatrics, LLC

Tracy received her B.Ed and M.Ed from the University of Virginia. Wahoo-wa! She is excited to be a new member with the Spectrum Pediatrics team and help children communicate with those that they love. Tracy has worked with numerous kids with a variety of needs throughout her years as a speech pathologist including autism spectrum disorder, receptive and expressive language delays, articulation/phonology difficulties, apraxia, and pragmatic skills deficits. She finds it rewarding to see the small successes turn into amazing progress with each child!

Spectrum Pediatrics is a therapist-owned practice that aims to provide the highest quality services to children in the Northern Virginia area. Spectrum Pediatrics was founded by Jennifer Berry, MS, OTR/L and Maureen Burnham, MS, CCC-SLP in 2004

PediaStaff is Hiring!

All JobsPediaStaff hires pediatric and school-based professionals nationwide for contract assignments of 2 to 12 months. We also help clinics, hospitals, schools, and home health agencies to find and hire these professionals directly. We work with Speech-Language Pathologists, Occupational and Physical Therapists, School Psychologists, and others in pediatric therapy and education.