Focus on Bilingualism: The Complexities of Being Bilingual

By: Alejandro Brice, Ph.D, CCC-SLP, Ellen Kester, Ph.D., CCC-SLP and Roanne Brice, Ph.D., CCC-SLP

Introduction

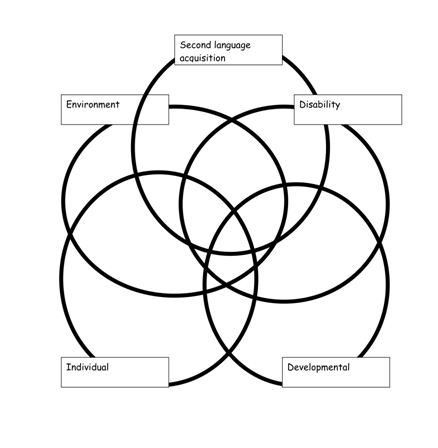

Bilingual or dual language acquisition is a process that differs from monolingual development (Brice & Brice, 2009). It involves more layers that affect ultimate acquisition including:

a) second language acquisition factors;

b) environmental factors;

c) individual factors;

d) developmental factors, and,

e) if the child has disabilities, then disabilities are also confounding factors.

This article will briefly present these overlaying components and provide suggestions for speech-language pathologists in promoting bilingualism. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Interaction of Bilingual Factors.

Second Language Acquisition

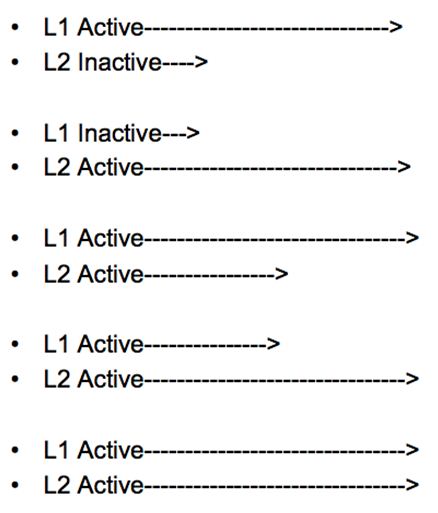

Learning a second language is not a straight forward additive process to English. It does not involve a one-to-one correspondence. Grosjean (1989) refers to language modes or the state to which two languages are active in bilingual communication (e.g., perception, processing, and speaking). A second language cannot be completely deactivated. Therefore, language mode refers to the continuum of activation of both languages. See Figure 2 below.

As can be seen from this illustration, bilingual language communication involves whether the two languages are active or inactive and the degrees of proficiency in each of the languages. Proficiencies in first or second languages are complex issues.

It appears from initial research that bilingual infants experience extra language demands and a consequent limitation on cognitive resources. As result, bilingual children may experience language deceleration in both of their languages (Fabiano-Smith & Barlow, 2009; Paradis & Genessee, 1996). A bilingual child may lag in her/his development compared to monolingual speakers of either language (e.g., Spanish or English). But do the bilingual speakers catch-up or attain ultimate proficiency in both of their languages?

Research investigating speech perception abilities of bilingual adults indicate that some bilinguals are capable of attaining equal or ultimate attainment abilities in their second language (Brice & Brice, 2008). However, this ability was found among only middle bilinguals (i.e., sequential bilinguals who had begin their English acquisition between 9-15 years of age and also been exposed to advanced English levels for at least six years). It should be noted that most bilinguals achieve, at minimum, functional abilities in both languages. Consequently, it appears that adequate exposure and maintenance to both languages is requisite for English development.

Children can and do “fall between the cracks.” Language interference, language loss, and fossilization can and do occur with second language acquisition. Language interference is the negative influence that a first language may have upon learning a second language. It is the imposition of L1 onto L2. An example is where the Spanish speaker may pronounce a “th” as a “d” sound. This is because the “th” sound does not occur in Spanish of the Americas (excluding Castilian Spanish from Spain). The bilingual speaker will utilize a close approximation from their native language (L1). This interference is normal and typically will disappear given time, adequate English exposure, and perhaps instruction (Cummins, 1984). Language loss is when one of the two languages (typically, the native language) diminishes in growth or disappears. Some of our research with bilingual elementary aged students (3rd, 4th, 5th grade students) indicate that this occurs with typically developing students (i.e., no disabilities present) (Brice & Leung, in preparation). Language loss has been well documented by others (Selinker, 1991). Please note that bilingual children can also shift toward greater English vocabulary with increased English exposure (Kohnert & Bates, 2002; Kohnert, Bates, & Hernandez, 1999).

Language fossilization is where growth in English (or the L2) stagnates. Both language loss and fossilization are real possibilities for bilingual children. Acquiring English and maintaining the native language are not guarantees for children.

Environmental Factors

According to Wong-Fillmore (1992), bilingualism (i.e., high levels of proficiency and balanced abilities) is possible only when certain conditions are met:

- Need to communicate. The child and others must fulfill communicative intents. Motivation and desire to communicate are integral ascpect. Speech-language pathologists must provide opportunities for real communication.

- Access to language from speakers of that language. Bilingual individuals must have access to English and this English must be of a high level.

- Interaction, support, feedback from speakers of that language must be present. This interaction and feedback must be adequate for learning to occur.

- Time. It takes considerable time to adequately learn a second language, especially beyond just conversational abilities (Cummins, 1984; Thomas & Collier, 2002). It may take from 4-6 years or 5-7 years to acquire native-like abilities for classroom language. Thomas and Collier state that this occurs only if the child has a strong base in their first language; otherwise, it may take up to 10- 13 years. Again, support of the native language is crucial for English development.

Individual and Developmental Factors

The child’s cognitive aptitude and also stages in their language, cognitive, and physical development play roles in second language learning. It is apparent that gifted and talented students may experience accelerated learning in acquiring English (Brice, Shaunessy, Hughes, Mchatton, & Ratliff, 2008). Just as developmental stages affect first language development; these same processes and stages also affect second language acquisition. It is beyond the scope of this article to detail all these processes. However, it must be mentioned that the interaction of developmental stages among two developing language systems is more complex and varied than with monolingual development.

Disability Factors

The most perplexing question among monolingual speech-language pathologists is whether bilingual children with disabilities can acquire both languages. Clinical experiences and research support the notion that these children are fully capable of language and cognitive growth in their two language systems (Kohnert, 2008). The limiting factor appears to be the extent of their disability and not their two languages. Research supports the notion that bilingualism may be an advantage (Hakuta & Bialystok, 1994).

Strategies for Promoting Bilingualism

The following points are for making learning a second language an additive process.

- SLPs, should make learning English in the classroom and in social environments a positive experience in which both languages are valued. High-level language and thinking should be involved. Bilingual children should be encouraged to participate in verbal and literacy problem-solving tasks. SLPs should verbalize how they solve problems to provide a cognitive model.

- Bilingualism should be promoted in both the home and school. Children should be allowed to speak either Spanish or English when it facilitates their communication (Brice & Perkins, 1997). The children’s comfort level for using English should be allowed to mature and not be a forced issue.

- Children should have well-developed Spanish skills before learning English (Wong-Fillmore, 1992).

- Opportunities for reading and writing in both Spanish and English should be provided. Parents should be encouraged to read to their children in Spanish. Emergent literacy skills, knowing about the written word and books, are generalizable across languages. Appreciation of books is not language specific.

- Ample opportunities to interact with native Spanish speakers should be provided to maintain L1.

- The children should receive appropriate instruction in English. Learning English should reflect natural language usage.

- Children should be allowed to make errors in English as this is a natural phenomena.

Conclusion

Working with second language learners with disabilities provides extra challenges for speech-language pathologists. Some of these challenges are unique; yet, provision of speech and language therapy has never been an easy task. Consequently, we must provide high quality services to all of our clients, students, and patients. It is in our nature as speech-language pathologists to overcome language barriers be it a result of bilingualism, disability, or both.

References

Brice, A. & Brice, R. (2009). (Ed.s). Language development: Monolingual and bilingual acquisition. Old Tappan, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Brice, A. & Brice, R. (2008). Examination of the critical period hypothesis and ultimate attainment among Spanish-English bilinguals and English-speaking monolinguals. Asia Pacific Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing, 11(3), 143-160.

Brice, A., & Leung, C. (in preparation). First and second language vocabulary among elementary school students.

Brice, A., Shaunessy, E., Hughes, C., Mchatton, P. A., & Ratliff, M. A. (2008). What language discourse tells us about bilingual adolescents: A study of students in Gifted programs and students in General Education programs. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 32(1), 7-33.

Cummins, J. (1984). Bilingualism and special education : Issues in assessment and pedagogy. San Diego: College-Hill Press.

Fabiano-Smith, L. & Barlow, J. (2009). Interaction in bilingual phonological acquisition: Evidence from phonetic inventories. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 31 (1). 1-17.

Grosjean, F. (1989). Neurolinguists, beware! The bilingual is not two monolinguals in one person. Brain and Language, 36, 30–15.

Hakuta, K., & Bialystok, E. (1994). In other words: The science and psychology of second-language acquisition. New York: BasicBooks.

Kohnert, K., & Bates, E. (2002). Balancing bilinguals II: Lexical comprehension and cognitive processing in children learning English and Spanish. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 45, 347-359.

Kohnert, K., Bates, E., & Hernandez, A. (1999). Balancing bilinguals: Lexical-semantic production and cognitive processing in children learning Spanish and English. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42, 1400-1413.

Kohnert, K. (2008). Second language acquisition: Success factors in sequential bilingualism. The ASHA Leader, 13 (2), 10-13.

Pardis, J., & Genessee, F. (1996). Syntactic acquisition in bilingual children: Autonomous or independent? Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 18, 1-25.

Selinker, L. (1991). Along the way: Interlanguage systems in second language acquisition. In L. M. Malavé & G. Duquette (Eds.), Language, culture and cognition (pp. 23-35). Bristol, PA: Multilingual Matters.

Thomas, W.P. & Collier, V. P. (2002). A national study of school effectiveness for language minority student’s long term academic achievement. Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence and the Office of educational Research Improvement. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 475048).

Wong-Fillmore, L.W. (1992). When does 1+1 =<2? Paper presented at Bilingualism/bilingüismo: A clinical forum, Miami, FL.

This Month’s Featured Authors:

Alejandro Brice, Ph.D., CCC-SLP University of South Florida St. Petersburg

Ellen Kester, Ph.D., CCC-SLP Bilinguistics, Inc.

Roanne Brice, Ph.D., CCC-SLP University of Central Florida

Many thanks to Dr. Alejandro E. Brice for providing this article for this months newsletter

Dr. Alejandro E. Brice is an Associate Professor at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg in Secondary/ESOL Education. His research has focused on issues of transference or interference between two languages in the areas of phonetics, phonology, semantics, and pragmatics related to speech-language pathology. In addition, his clinical expertise relates to the appropriate assessment and treatment of Spanish-English speaking students and clients. Please visit his website at http://scholar.google.com/citations?user=LkQG42oAAAAJ&hl=en or reach him by email at [email protected]

Dr. Ellen Kester is a Founder and President of Bilinquistics, Inc. http://www.bilinguistics.com. She earned her Ph.D. in Communication Sciences and Disorders from The University of Texas at Austin. She earned her Master’s degree in Speech-Language Pathology and her Bachelor’s degree in Spanish at The University of Texas at Austin. She has provided bilingual Spanish/English speech-language services in schools, hospitals, and early intervention settings. Her research focus is on the acquisition of semantic language skills in bilingual children, with emphasis on assessment practices for the bilingual population. She has performed workshops and training seminars, and has presented at conferences both nationally and internationally. Dr. Kester teaches courses in language development, assessment and intervention of language disorders, early childhood intervention, and measurement at The University of Texas at Austin. She can be reached at

[email protected]

Dr. Roanne G. Brice is the Assistant to the Chair for the Department of Child, Family and Community Sciences at the University of Central Florida. Her research interests have focused on language and beginning literacy skills in bilingual children and students with disorders/disabilities. In addition to teaching at the university level, Dr. Brice has been an itinerant and self-contained classroom speech-language pathologist as well as a general education classroom teacher. She may be reached at [email protected]

PediaStaff is Hiring!

All JobsPediaStaff hires pediatric and school-based professionals nationwide for contract assignments of 2 to 12 months. We also help clinics, hospitals, schools, and home health agencies to find and hire these professionals directly. We work with Speech-Language Pathologists, Occupational and Physical Therapists, School Psychologists, and others in pediatric therapy and education.