Self-Management for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders

By: Lee A. Wilkinson, PhD, NCSP

Introduction

The dramatic increase in the number of school-age children identified with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) has created a pressing need to design and implement positive behavioral supports in our schools’ classrooms. Autism is much more prevalent than previously thought, especially when viewed as a spectrum of disorders. For example, recent estimates suggest that ASDs now affect approximately 1 to 2 % of the school-age population (Wilkinson, 2010). As a result, school-based support professionals are now more likely to be called on to consult with teachers and parents on how to manage the behavioral challenges of learners with ASD than at any other time in the recent past.

Although there is no single effective behavioral intervention, evidence-based strategies such as self-management have shown considerable promise in addressing the attention and concentration difficulties and poor behavioral regulation of learners with ASD (Callahan & Rademacher, 1999; Wilkinson, 2005, 2008, 2010). This article illustrates the use of self-management as a positive and practical classroom strategy for enhancing the independence, self-reliance, and school adjustment of students on the autism spectrum.

Self-Management

A great deal of research has accumulated over the past two decades that demonstrates the effectiveness of teacher-managed interventions in responding to children’s learning and behavioral challenges. Research indicates that interventions involving the external manipulation of antecedents and consequences have, in general, been successfully applied to a wide range of classroom problems (Gresham, 2004; Stage & Quiroz, 1997). However, there are limitations to these management approaches. For example, teacher-directed programs focus more on controlling behavior than on helping students acquire the skills needed to self-regulate their behavior and achieve greater levels of independent functioning. In addition, these behavior management techniques can be intrusive and require teachers to expend valuable instructional time applying external contingencies (Shapiro & Cole, 1994).

Self-management strategies are an alternative to teacher-managed contingency procedures for students with and without exceptionalities. They have been implemented effectively for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, learning disabilities, disruptive behavior disorders, and autism spectrum disorders (Barry & Messer, 2003; Hoff & DuPaul, 1998; Callahan & Rademacher, 1999; Lee, Simpson, & Shogren, 2007; L. K. Koegel, Harrower, & Koegel, 1999; McDougall, 1998; Odom, Brown, Frey, Karasu, Smith-Canter, & Strain, 2003; Shapiro, Miller, Sawka, Gardill, & Handler, 1999; Rock, 2005; Todd, Horner, & Sugai, 1999; Smith & Sugai, 2000;; Wilkinson, 2005).

Definition of Self-Management

Self-management generally involves activities designed to change or maintain one’s own behavior. In its simplest form, students are instructed to (a) observe specific aspects of their own behavior and (b) provide an objective recording of the occurrence or nonoccurrence of the observed behavior (Cole & Bambara, 2000; Shapiro & Cole, 1994). This self-monitoring procedure involves providing a cue or prompt and having students discriminate whether or not they engaged in a specific behavior at the moment the cue was supplied. Research indicates that focusing attention on one’s own behavior and the self-recording of these observations can have a positive “reactive” effect on the behavior being monitored (Cole, Marder, & McCann, 2000).

Advantages of Self-Management

One of the prominent features of students with ASD is an absence of, or a poorly developed set of self-management skills. This includes difficulty directing, controlling, inhibiting, or maintaining and generalizing behaviors required for adjustment without the external support and structure from others. Learning to engage in a positive behavior in place of an undesirable one can have the collateral effect of improving academic performance and social adjustment. Self-management has the advantage of teaching students to be more independent, self-reliant, and less dependent on external control and adult supervision (Callahan & Rademacher, 1999; R. L. K Koegel et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2007; Odom et al., 2003; Wilkinson, 2008, 2010).

Many children with ASD do not respond well to typical “top down” approaches involving the external manipulation of antecedents and consequences. Self-management provides students with an opportunity to participate in the development and implementation of their behavior management programs, an important consideration for many students with ASD.

Self-management interventions can also help minimize the potential for the power struggles and confrontations often experienced with the implementation of externally-directed techniques.

Designing a Self-Management Plan

The following steps provide a general guide for preparing and implementing a self-management plan in the general education classroom. They should be modified as needed to meet the individual needs of the student.

Step 1: Identify preferred behavioral targets. The initial step is to identify and operationally define the target behavior(s). This involves explicitly describing the behavior so that the student can accurately discriminate its occurrence and nonoccurence. For example, target behaviors such as “being good” and “staying on task” are broad and relatively vague terms, whereas “raising hand to talk” and “eyes on paper” are more specific. When developing operational definitions, it is also useful to provide exact examples and nonexamples of the target behavior. This will help students to recognize when they are engaging in the behavior(s).

While self-management interventions can be used to decrease problem behavior, it is best to identify and monitor an appropriate, desired behavior rather than a negative one. Describe the behavior in terms of what students are supposed to do, rather than what they are not supposed to do. This establishes a positive and constructive alternative behavior. Here are some examples of positive target behaviors:

- Cooperate with classmates on group projects by taking turns.

- Follow teacher directions and raise hand before speaking.

- Sit at desk and work quietly on the assignment.

Step 2: Determine how often students will self-manage their behavior. An interval method is usually recommended for monitoring off-task behavior, increasing appropriate behavior and compliance, and decreasing disruptive behavior (Cole et al., 2000). Typically, the interval will depend on the student’s characteristics, such as age, cognitive level, and severity of behavior. Some students will need to self-monitor more frequently than others. For example, if the goal is to decrease a challenging behavior that occurs frequently, then the student will self-monitor a positive, replacement behavior more often. Interval lengths should be based on students’ individual ability levels and degree of behavioral control.

Once the frequency of self-monitoring is determined, a decision is made as to the type of cue that will be used to signal students to self-observe and record their behavior. In classroom settings, this generally involves the use of a verbal or nonverbal external prompt. There are several types of prompts that can be used to signal students to monitor their behavior in the classroom: verbal cue; silent cue, such as a hand motion; physical prompt; timing device with a vibrating function; kitchen timer; watch with an alarm function; or prerecorded cassette tape with a tone. The type of cue will depend on the ecology of the classroom and the students’ individual needs and competencies. Regardless of the prompt selected for the student, it is important that it be age appropriate, unobtrusive and as nonstigmatizing as possible.

Step 3: Meet with the student to explain the self-management procedure. Student participation is important as it increases “ownership” and active involvement in the plan. Once the target behavior has been defined and frequency of self-monitoring decided, discuss the benefits of self-management, behavioral goals, and specific rewards or incentives for meeting those goals with the student. Providing the student with a definition of behaviors to change, as well as commenting on the benefits of managing one’s own behavior will increase the likelihood of a successful intervention. Students might be told “self-management means being responsible for your own behavior so that you can succeed in school and be accepted by others.” Asking students to select from a menu of reinforcers or identify at least 3 preferred school-based activities also helps to ensure that the incentives are truly motivating and rewarding.

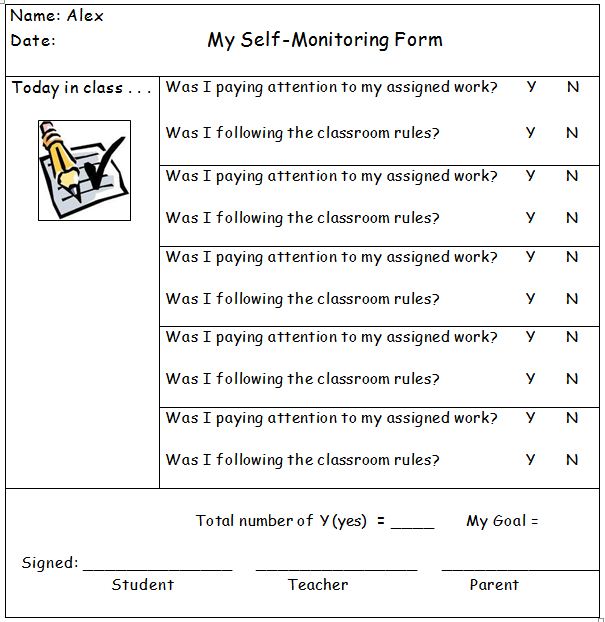

Step 4: Prepare a student self-recording sheet. The most popular self-management recording method in school settings is the creation of a paper-and-pencil checklist or form. This form lists the appropriate academic or behavioral targets students will self-observe when they are cued at a specified time interval. For example, a goal statement such as “Was I paying attention to my seatwork?” would be included as a question to which the student records a response. When developing the form, it is important to consider each student’s cognitive ability and reading level. For young students and those with limited reading skills, pictures can be used to represent the target behaviors or response to the goal statement/question.

Step 5: Model the self-management plan and practice the procedure. The use of modeling, practice, and performance feedback is critical to teaching students to self-manage their behavior. After the target behaviors and goals are identified, frequency of self-monitoring determined, and the data recording form developed, the self-management process is demonstrated for the student. This includes modeling the procedure and asking students to observe while the teacher simulates a classroom scenario. Students are encouraged to role-play both desired and undesired behaviors at various times during practice, and to accurately self-observe and record these behaviors. The teacher also practices rating the target behavior to become familiar with the self-monitoring form and make students aware that others are checking their monitoring. Accuracy is determined by comparing student ratings with those of the teacher made on the same self-recording form. Students are provided with feedback on their progress and when necessary, given further opportunity to practice. Students practice until they demonstrate mastery of the procedure by meeting a minimum criterion for accuracy (e.g., 80% accuracy for two out of three consecutive instructional sessions).

Step 6: Implement the self-management plan. Once reliability with the self-monitoring procedure is established, the students rate their behavior on the self-recording sheet at the specified time interval in the natural setting. For example, students might be prompted (cued) to record their behavior at 10-minute intervals during independent or small group instruction in their classroom. When cued, the student responds to the self-observation question (e.g., Was I paying attention to my seat work?) by marking Y (yes) or N (no) on the recording sheet. Students may also be required to maintain a designated level of accuracy (e.g., no more than one session per week with less than 80% accuracy) during implementation of the self-management procedure. If the level is not maintained, booster sessions are provided to review target behavior definitions and the self-monitoring process.

Step 7: Meet with the student to determine whether goals were attained. A brief conference is held with the student each day to determine whether the behavioral goal was met and to compare teacher and student ratings. Students are rewarded from their reinforcement menus or with the agreed upon incentives when the behavioral goal is met for the day. If the behavioral goal is not reached, students are told they will have an opportunity to earn their reward during the next day’s self-monitoring session. When the students’ ratings agree with their teacher (e.g., 80% of the time), they are provided with verbal praise for accurate recording. Accuracy checks can occur more frequently at the beginning of the intervention and reduced once the target behavior is established.

It is important to note that the teachers’ ratings are the accepted standard. It is not unusual, especially at the start of a self-management plan, for teacher and student to have disagreements about the accuracy of the ratings. If this occurs, it is best to initiate a conference with the student to help clarify the target behavior and attempt to resolve the discrepancy. Occasionally, students may continue to argue with the teacher about the ratings. If this problem persists, then the self-monitoring procedure should be discontinued, as it is unlikely to be an effective intervention.

Step 8: Provide the rewards when earned. An important component of self-management is the presence of a reward. Although self-monitoring can be implemented without incentives, goal-setting and student selection of reinforcement makes the intervention more motivating and increases the likelihood of positive reactive effects. Therefore, it is critically important that the agreed upon incentives be provided when students have met their daily behavioral goal.

Step 9: Incorporate the plan into a school-home collaboration strategy. Parents play an essential role in developing and implementing behavior management plans for learners with ASD. The self-recording form is sent home each day for their signature to ensure that the student receives positive reinforcement across settings. It’s usually best to have a phone or personal conference with parents before beginning the intervention to explain the purpose of self-monitoring and explain how they can positively support the intervention at home (such as using their child’s special interest as a reward).

Step 10: Fade the intervention. The procedure may gradually be faded once the desired behavior is established in order to reduce reliance on external cueing. This typically involves extending the interval between prompts or reducing the number of intervals. The target behaviors are continuously monitored to determine compliance with the procedures and the need to readjust the fading process. The ultimate goal is to have students self-monitor their behavior independently and without prompting. Once students achieve competency with self-management, they can apply their newly learned self-regulation skills to other situations and settings, thereby facilitating generalization of appropriate behaviors in future environments with minimal or no feedback from others.

Case Vignette: Alex

Alex was an 8-year-old student with a diagnosis of ASD and a history of difficulty in the areas of appropriateness of response, task persistence, attending and topic maintenance. Challenging social behaviors reported by Alex’s teacher included frequent off-task behavior, arguing with adults and peers, temper tantrums, and noncompliance with classroom rules. Few students wanted to sit or work with Alex due to his frequent intrusive and disruptive classroom behavior. Among Alex’s strengths were his well-developed visualization skills and memory for facts and details. Several interventions had been tried, but without success, including verbal reprimands, time-out and loss of privileges. The school psychologist worked with Alex’s teacher to design and implement a self-management intervention in an effort to reduce Alex’s challenging classroom behavior.

Behavior ratings completed by his teacher indicated that Alex was disengaged and noncompliant for approximately 60% of the time during independent seatwork and small group instruction. On-task behavior and compliance with classroom rules were identified as the target behaviors. The self-management procedure consisted of two primary components: (a) self-observation and (b) self-recording. Self-observation involved the covert questioning of behavior (e.g., Was I paying attention to my assigned work?) and self-recording the overt documentation of the response to this prompt on a recording sheet. Alex was told “self-management means accepting responsibility for managing and controlling your own behavior so that you can accomplish the things you want at school and home.” He was also given an example of the target behaviors to be self-monitored. “On-task” behavior was defined as (a) seated at own desk, (b) work materials on desk, © eyes on teacher, board, or work, and (d) reading or working on an assignment. “Compliant” was defined as following classroom rules by (a) asking appropriate questions of teacher and neighbor; (b) raising hand and waiting turn before speaking, © interacting appropriately with other students, and (d) following adult requests and instructions. Alex was instructed on how to accurately self-observe and record the target behaviors. His teacher read the goal questions on the self-recording form and provided examples of behavior indicating their occurrence or nonoccurrence. She also modeled the behaviors Alex needed to increase and demonstrated how to use the self-recording form to respond to the behaviors observed. Alex then practiced self-monitoring the target behaviors until he demonstrated proficiency with the procedure.

Following 3 days of instruction, the self-monitoring procedure was incorporated into Alex’s daily classroom routine. A self-recording form was taped to the upper right hand corner of his desk. Because he was the only student who was self-monitoring in the class and other students might be disturbed by a verbal cue, his teacher physically cued Alex by gently tapping the corner of his desk at 10-minute intervals during approximately 50-minutes of independent and small-group instruction. When cued, Alex covertly asked himself “Was I paying attention to my assigned work?’ and “Was I following my teacher’s directions and classroom rules?” He then marked his self-recording form with a Y (yes) or N (no), indicating his response to the questions regarding the target behaviors. When he met his daily behavioral goals, Alex could make a selection from a group of his preselected incentives such as additional computer game time and access to a preferred game or activity. The completed self-recording form was then sent home for his parent’s signature, so they could review Alex’s behavior and provide a reward contingent upon meeting his behavioral goals. Figure 1 provides an example of Alex’s self-recording form with behavioral goal questions.

Note: Adapted with permission from Wilkinson, L. A. (2010). A best practice guide to Assessment and intervention for autism and Asperger syndrome in schools. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

The self-monitoring intervention continued for approximately three weeks during which time Alex’s teacher continued to collect performance data. A “treatment integrity” checklist was also completed each day to ensure that all components of the self-monitoring intervention were implemented as planned.

When his teacher determined that Alex’s task engagement and compliant behavior had increased to 90%, the procedure was slowly faded by increasing the intervals between self-monitoring cues (e.g., 10 minutes, 15 minutes, and 20 minutes). Alex’s teacher continued to monitor the target behaviors to determine whether additional support (e.g., booster sessions) was needed to maintain his performance. The goal of the final phase of the plan was to eliminate the prompts to self-monitor and instruct Alex to keep track of his “own” behavior. Home-school communication continued via a daily performance report to help maintain his self-management independence and positive behavioral gains. Periodic behavioral ratings by Alex’s teacher indicated that task engagement and compliant behavior remained at significantly improved levels several weeks after the self-monitoring procedure was completely faded.

Discussion and Limitations

Despite the potential benefits of self-management, this strategy is not without some limitations. Self-management procedures are intended to complement, not replace, positive behavioral support (PBS) strategies already in place in the classroom. Likewise, they should not be considered as rigid and inflexible procedures, but rather a “framework” in which to design and implement effective interventions to facilitate the inclusion of students with ASD and other disabilities in general education settings. For example, the self-monitoring plan described in Alex’s case vignette represents only one of the many possible ways that self-management procedures can be utilized in the classroom.

Shifting from an external teacher-managed approach to self-management can present some obstacles. As with other interventions, self-management strategies can fail due to student and teacher resistance, poor training, and/or a lack of appropriate reinforcement (Cole et al., 2000). Successful implementation of self-management procedures requires that students be motivated and actively involved in the self-monitoring activities. Similarly, teachers considering implementation of a self-management intervention will need to invest the time required to identify behavior needs, establish goals, determine reinforcers, and teach students how to recognize, record, and meet behavioral goals. In order for self-management to be an effective intervention, the procedures must be acceptable to all parties and implemented as planned (with integrity). If not fully supported, it is better to focus on a more suitable behavior management approach.

Self-management interventions are not appropriate for every child with ASD. Some procedures will meet the needs of individual students better than others. For example, severe behaviors may require a comprehensive approach using multiple intervention techniques. Students also react differently to self-management procedures. Some students will find being in control a motivating and reinforcing activity. For others, self-management procedures may actually be a time-consuming distraction. As with any behavioral intervention, a thorough understanding of the student’s problem and needs should precede and inform the selection of a specific behavior management strategy.

Concluding Comments

Supporting children with ASD in the general education classroom presents a unique challenge to the teachers and schools that serve them. However, many students will make progress and adapt to the classroom setting if provided with the appropriate interventions and behavioral supports. By learning self-management techniques

- learners with ASD become more independent, self-reliant, and responsible for their own behavior,

- have an opportunity to participate in the design and implementation of their own behavior management programs, rather than traditional external contingency approaches, and

- develop a “pivotal” skill that facilitates generalization of adaptive behavior, supports autonomy, and has the potential to produce long lasting behavioral improvements across a range of contexts.

Self-management procedures are also cost efficient and can be especially effective when used as a component of a comprehensive service delivery approach involving functional assessment, social groups, curricular planning, sensory accommodations, and parent-teacher collaboration. Although the research on the effectivess of intervention strategies for children with autism is still in a formative stage, self-management is an emerging and promising technology for fostering independence and self-control for students on the autism spectrum.

References

Barry, L. M., & Messer, J. J. (2003). A practical application of self-management for students diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 5, 238-248.

Callahan, K., & Rademacher, J. A. (1999). Using self-management strategies to increase the on- task behavior of a student with autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 1, 117-122.

Cole, C. L., & Bambara, L. M. (2000). Self-monitoring: Theory and practice. In E. S. Shapiro & T. R. Kratochwill (Eds.), Behavioral assessment in schools: Theory, research, and clinical foundations (2nd ed., pp. 202-232). New York: Guilford Press.

Cole, C. L., Marder, T., & McCann, L. (2000). Self-monitoring. In E. S. Shapiro & T. R. Kratochwill (Eds.), Conducting school-based assessments of child and adolescent behavior (pp. 121-149). New York: Guilford Press.

Gresham, F. M. (2004). Current status and future directions for school-based behavioral interventions. School Psychology Review, 33, 326-343.

Hoff, K. E., & DuPaul, G.J. (1998). Reducing disruptive behavior in general education classrooms: The use of self-management strategies. School Psychology Review, 27, 290- 303.

Koegel, L. K., Harrower, J. K., & Koegel, R. L. (1999). Support for children with developmental disabilities in full inclusion classrooms through self-management. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 1, 26-34.

Lee, S., Simpson, R. L., & Shogren, K. A. (2007). Effects and implications of self-management for students with autism: A meta-analysis. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 22, 2-13.

McDougall, D. (1998). Research on self-management techniques used by students with disabilities in general education settings. Remedial and Special Education, 19, 310-320.

Odom, S. L., Brown, W. H., Frey, T., Karasu, N., Smith-Canter, L. L., & Strain, P. S. (2003). Evidence-based practices for young children with autism: Contributions from single- subject design research. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 18, 166- 175.

Rock, M. L. (2005). Use of strategic self-monitoring to enhance academic engagement, productivity, and accuracy of students with and without disabilities. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 7, 3-17.

Shapiro, E. S., & Cole, C. L. (1994). Behavior change in the classroom: Self-management interventions. New York: Guilford Press.

Shapiro, E. S., Miller, D. N., Sawka, K., Gardill, M. C., & Handler, M. W. (1999). Facilitating the inclusion of students with EBD into general education classrooms. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 7, 83-93.

Smith, B. W., & Sugai, G. (2000). A self-management functional assessment based behavior support plan for a middle school student with EBD. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 2, 209-217.

Stage, S. A., & Quiroz, D. R. (1997). A meta-analysis of interventions to decrease disruptive classroom behavior in public education settings. School Psychology Review, 26, 333-368.

Todd, A. W., Horner, R. H., & Sugai, G. (1999). Self-monitoring and self-recruited praise: Effects on problem behavior, academic engagement, and work completion in a typical classroom. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 1, 66-76.

Wilkinson, L. A. (2005). Supporting the inclusion of a student with Asperger syndrome: A case study using conjoint behavioural consultation and self-management. Educational Psychology in Practice, 21, 307-332.

Wilkinson, L. A. (2008). Self-management for high-functioning children with autism spectrum disorders. Intervention in School and Clinic, 43, 150-157.

Wilkinson, L. A. (2010). A best practice guide to assessment and intervention for autism and Asperger syndrome in schools. London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Study Questions

1. What is the major advantage of using self-management strategies over traditional behavioral interventions? Describe the pros and cons of self-management.

2. In what settings can self-management be used effectively? How have they been implemented in clinical and school-based settings with early childhood through high school age groups?

3. What specific skills or intervention goals can be self-monitored to reduce challenging behaviors and increase social, adaptive, and language/communication skills?

4. What should general education students be told about a classmate with ASD who is self-monitoring inappropriate behaviors?

5. How can self-management be incorporated into a school’s response-to-intervention (R-t-I) plan to address a student’s interfering behaviors?

Featured Author: Lee A. Wilkinson, EdD, PhD, NCSP

Lee A. Wilkinson, EdD, PhD, NCSP is an author, applied researcher, and practitioner. He is a nationally certified school psychologist, registered psychologist, and certified cognitive-behavioral therapist. Dr. Wilkinson is currently a school psychologist in the Florida public school system where he provides diagnostic and consultation services for children with autism spectrum disorders and their families. He is the author of the award winning book “A Best Practice Guide to Assessment and Intervention for Autism and Asperger Syndrome in Schools” published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers. Dr. Wilkinson can be reached at http://bestpracticeautism.blogspot.com.

dup 2119

PediaStaff is Hiring!

All JobsPediaStaff hires pediatric and school-based professionals nationwide for contract assignments of 2 to 12 months. We also help clinics, hospitals, schools, and home health agencies to find and hire these professionals directly. We work with Speech-Language Pathologists, Occupational and Physical Therapists, School Psychologists, and others in pediatric therapy and education.